By Arron Merat

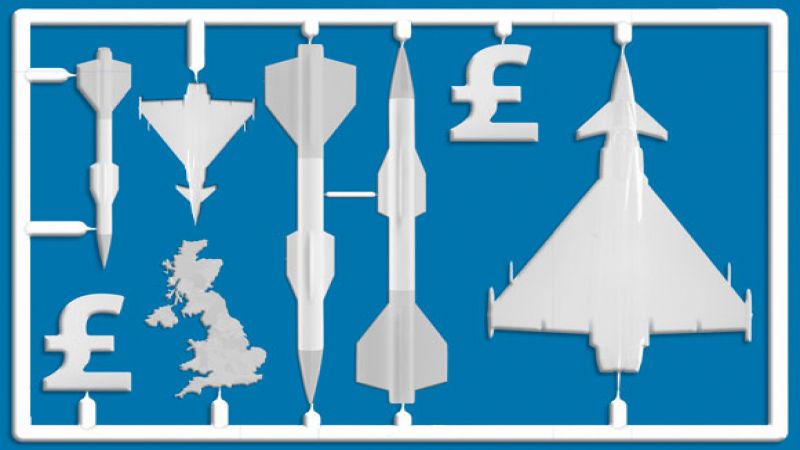

“I am investigating a suspicious, potentially illegitimate, call to an employee of a firm on whose behalf I am now calling,” said the man with the Scottish accent dialling from an unknown number. He refused to divulge his name or the firm to which he was connected, but it was clear that he was linked to Raytheon. Earlier that day I had placed a call—inadvertently interrupting a Secret Santa exchange—to a worker at the US defence giant’s arms factory in Glenrothes, Fife. It is the plant that puts the “smart” in the “smart bombs” that Saudi Arabia is dropping on Yemen.

Raytheon’s Scottish factory builds the electronics systems for precision-guided bombs. The factory’s signature line is circuit boards for the Paveway IV, a 500-pound, all-weather, laser-and-GPS-guided bomb. Raytheon has all sorts of customers, the RAF included. But since the Saudi Royal Air Force started bombing Yemen in 2015, these Paveways have also been much sought after by the Saudi government.

The war, which has left over 100,000 dead and millions displaced, costs the Saudi government an estimated £50bn a year, a significant chunk of which is spent on US and British weaponry that the UN says is being used to “target civilians… in a widespread and systematic manner.” Death, displacement, disease and acute hunger now form the contours of life for the 80 per cent of the Yemeni population—22m people—who are in need of humanitarian assistance. In late 2018, the UN’s top official in the Middle East at its children’s agency Unicef stated: “Yemen today is a living hell.”

Raytheon has used the slogan “strike with creativity,” and its precision bombs have been discovered in the wreckage of hundreds of civilian sites in Yemen including hospitals, schools and infrastructure indispensable to the civilian population such as granaries, groundwater pumps and water tanks. While Raytheon is not, of course, responsible for any particular decision to bomb civilian targets, it does have to abide by the law when it comes to the export of weapons to those countries engaged in dirty wars. And responsibility for overseeing those laws lies squarely with the government.

Ministers claim that the British arms trade is regulated by “one of the most robust arms export control regimes in the world.” Legally, arms cannot leave Britain if there is a “clear risk” that they could be used to deliberately or recklessly target civilians. As foreign secretary, when being asked about arms exports to Saudi Arabia in October 2016, Boris Johnson insisted “we take our arms export responsibilities very seriously indeed,” adding the “most relevant test” in export licensing was the risk of a “violation of international humanitarian law.”

But on 20th June 2019 the Court of Appeal found that, for Saudi Arabia, the then-trade secretary Liam Fox had—with the involvement of the former and then serving foreign secretaries, Johnson and Jeremy Hunt—unlawfully signed off on arms exports without properly assessing the risk to civilians. The judgment revealed that in early 2016 a quiet adjustment had been made to licensing procedures, such that hundreds of allegations of Saudi Arabia attacking civilians were not effectively considered in such decisions. The effect was that the export-control laws designed to protect civilians from British weapons were not being properly applied—and Johnson’s reassurances to parliament came months after the constraints had

been weakened.

The court ruling prompted the government to suspend arms sales to Saudi Arabia. But that has not prevented Raytheon armaments from finding their way into the Saudi war. The export licences issued before the ruling have not been revoked, and the government has continued to issue Raytheon UK, which describes itself as a “fully owned subsidiary of Raytheon in the US,” with new licences to export munition components to America. Indeed, in January this year junior trade minister Graham Stuart confirmed in an answer to a parliamentary question that already, in the short period since the court case, “seven Standard Individual Export Licences… [had] been granted to Raytheon UK… for export to the US.” The components potentially covered by the category of the two-year licences included missiles, bombs, torpedoes and rockets. Once components reach the US, there is no block on them being incorporated into weapons that can be sold on to Saudi—indeed, the Trump administration recently vetoed Congressional attempts to impose blocks on arms sales to Saudi Arabia.

“Everyone knows that for the Gulf, it’s a free for all,” a serving manager at Raytheon UK told me, referring to arms exports to Saudi Arabia and other monarchies such as the UAE and Bahrain that constitute its war coalition. The Saudis “have got more money than God. The government is not going to let Yemen get in the way of this.”

At last September’s DSEI arms fair in London, I asked Adam Fico, Raytheon’s head of government relations, how the firm’s code of conduct—“do the right thing,” “respect human rights”—squares with its products being found in the wreckage of schools and hospitals. After evading the question several times, he said, “I can tell you I certainly didn’t kill anybody” and rushed away into a tiny room marked “staff only.”

In a statement, Corinne Kovalsky, Raytheon’s global relations vice president in the US, told me: “It’s not our place to comment on the military actions of our allies, partners and customers. What I can tell you is that prior to exporting military and security items, proposed sales are subject to review by the US Departments of State and Defence and the Congress of the United States. They are charged with advancing US national security and foreign policy by determining if proposed foreign military sales serve US interests.”

Back in Glenrothes, inside Raytheon’s factory fence, topped with rotating anti-climb spikes, staff are not specifically told the purpose of the product they are manufacturing. One former manager at the site told me his team would be given “a drawing and a set of files that allows you to assemble it,” but wouldn’t know exactly what the finished product would be. “There’s a lot of secrecy around it within the company… the products that we built were just a part number; they were all given codenames.” He described the technology that powers the bombs as “the Coca-Cola secret recipe… You have your wee section and you don’t know what the final product does.” Which is to say, most of those within Raytheon almost certainly do not know what they are making. The company, after all, manufactures a wide variety of different systems from radar and reconnaissance to precision weapons.

During my week in Glenrothes, and the months spent researching this story, Raytheon—as that mysterious phone call suggests—seems to have done its best to put me off. One Raytheon employee said they had been instructed not to talk to me. MPs on the arms export controls committee have had a similarly tough time getting answers out of Raytheon—its executives declined to appear in front of the committee last year.

But it is clear that this is a town torn by its contribution to a faraway conflict. Some wrestle with it, some ignore it, while for some families in an economically depressed region keeping a job inevitably weighs more heavily than the moral questions of war.

While arms making has declined in Britain since the 1980s, government intervention has kept it more buoyant than other manufacturing industries. Following the Brexit vote, the newly founded Department for International Trade, which licenses arms exports, announced that it would work to expand Britain’s arms trade. The government spends up to £1bn a year on subsidising the defence sector and has a team of over 100 civil servants dedicated to promoting arms sales internationally. During the annual government-organised arms shows soldiers are paid to work as “escort officers” to pick up delegations from scores of countries from their hotels and take them shopping. The official pressure to boost exports runs the risk of encouraging sales to governments that use their weapons for repression at home and suppression abroad.

Just south of extinct volcanic features in central Fife lies the ancestral land of a family of Scottish aristocrats named Rothes, whose forebearer John Leslie, the 1st Duke of Rothes, was a confidant of Charles II. At the end of the Second World War, the British government set out to build a town there, and out of the Rothes’ estate grew Glenrothes (Rothes’ valley), one of around a dozen new towns of the era.

“You’d rather be a lifer than a Fifer,” goes the self-deprecating refrain about life on this fertile peninsula north of Edinburgh. Outsiders have also been known to poke fun at Glenrothes—a Glasgow-based architecture magazine awarded it the Carbuncle Award in 2009 for being “the most dismal town in Scotland.”

The original vision was largely about coal production—it was already falling in Lancashire, and London sought to maintain the UK’s independence in energy by developing deposits in Fife. Tinged with utopianism, the Glenrothes Development Corporation (GDC), a quango, built the town from 1948 and helped run it for most of its life. The deep coal mine was opened in 1958 by Queen Elizabeth, dressed in a white boiler suit, a white headscarf and a white miner’s helmet. Roundabouts and dual carriageways bisect several unique “precincts,” low-rise cul-de-sacs. One called “Macedonia,” for example, was built according to modernist fashions at the time: flat-roofed houses, overlooking mini-stone henges, engraved with dinosaurs, hippos and crocodiles. Warehouse spaces dotted the town offering work in light manufacturing, from making supermarket trollies to machines for the mines. There was a smart community-owned bowling alley. The hope of work attracted incomers, particularly from declining pits in Ayrshire and Glasgow. However, a second coal boom in Fife was not to be; the Rothes Colliery was forced to close because of flooding in 1964.

The GDC had been looking to California for inspiration as it sought to create skilled electronics jobs in the area. Endowed with millions of pounds by central government to encourage inward investment, it offered major financial inducements to US corporations, marketing Glenrothes on its clean air, necessary for the chemical processes involved in microelectronics fabrication. American electronics companies, which had become giants during the Second World War, came for cheap land, skilled labour and an opportunity to expand into a European economy whose recovery from the war was still picking up pace.

“Beggars can’t be choosers,” glibly explained Henry McLeish, the former First Minister of Scotland, who lived in Glenrothes for 30 years. “America was out there. If you could go and impress them you might get significant investment and that would bring jobs.”

Glenrothes became the centre of a Scottish electronics boom, which at its peak brought 100,000 jobs. This boom, that started in the 60s and peaked in the 80s, was drolly named “Silicon Glen.” While most coal towns were dealt a final blow during the 1984-85 miners’ strike, Glenrothes had found a new path to prosperity.

But by the end of the 1990s, following US corporate consolidations coupled with the outsourcing of UK manufacturing, Silicon Glen all but vanished. Raytheon UK, which employs around 600 people in Glenrothes, is today the only substantial electronics firm left in Fife. The firm is said to have held onto the Glenrothes factory because it had developed an innovative “wafer fab” technology, a means to fabricate circuit boards that was deemed to have become the “tribal knowledge” of Fife’s workers.

The fall of Silicon Glen took an enormous toll on Glenrothes’ workforce as people were laid off and forced into the lower paid service sector. Although a strong streak of civil pride runs among many residents, the town has suffered from acute economic decline for the past two decades. The result has been a slowly unfolding tragedy. Food banks have popped up, one with a sign advising would-be thieves that “there is no lead on this roof.” One in three children live in poverty.

The cheerless Kingdom shopping arcade in the town centre is dominated by bargain stores, betting shops and debt relief agencies. “They open for a month and then they close down,” remarks David, an unemployed 19-year-old, outside the Golden Acorn, the Wetherspoon pub that backs onto the shopping centre. “Glenrothes has suffered big time… There’s no nightlife and the local economy is gone. I’m facing imminent homelessness… Other than the Asda, there’s only one place to buy men’s clothes and it’s crap,” he adds, referring to a Scottish clothing chain store with the tagline: “Spend a little. Get a lot.”

“The great problem of Glenrothes and poverty more generally,” McLeish tells me, “is that it used to be people out of work getting benefits, now its people in work, in poverty and receiving [top-up] benefits. Glenrothes is a microcosm of what is happening across the central belt of Scotland, the north of England and much of the rest of the country.”

Other than Fife Council, Raytheon is the biggest employer in Glenrothes and also seen as the best, which may be why the denizens of the town are mostly reluctant to speak ill of the firm; “It’s the golden goose,” said a retiree drinking at the Golden Acorn. He acknowledged that he has family working at the firm, which sells electronic systems to both civilian buyers and also the RAF in this country. “It’s decent work working on those boards. And there’s not much of that around here anymore.”

Still, there are others in the town who are unhappy about the presence of the Raytheon factory. A pall fell across the face of some locals at the mention of the firm. “It’s not for me to say. I don’t know anything about them,” said a visibly nervous butcher. “We are completely separate to them.” A Muslim nurse told me that Raytheon was committing a sin by supporting Saudi Arabia in a “cruel action against women, children and elderly people in Yemen.” He added that his faith teaches that “he that kills, whatever the faith of the victim, kills all of mankind.”

But mostly people in Glenrothes feel ambivalent. At some point in any Raytheon conversation almost everyone will make the same gesture—two upturned palms symbolising a scale. On the one hand it provides the last, best jobs in a town that has fallen on hard times. On the other it does so through providing the technology that ends up being used to cause the deaths of many civilians 5,000 miles away.

On 20th September 2016, Saudi Arabia claimed it had killed rebel leaders in Al-Jawf Governorate, a remote and hardscrabble corner of Yemen. But when the UN and Mwatana, a Yemeni observation group, made independent visits to the site they discovered who had really been killed. The truck that was hit had been driven by a woman named Hamdah Taghin who was taking her two sisters-in-law to buy animal feed and grain following the harvest. With them were Hamdah’s five children, plus seven other children—the youngest just five months old. All 15 were killed when one of Raytheon’s Paveways struck. Three girls threshing crops nearby were also wounded, sustaining life-changing injuries. “I saw a very horrible sight that is hard to imagine,” a relative of one of the victims told Mwatana. “We would find a hand here and a foot there—all over the surrounding plants and trees—and we started collecting the body parts. People from neighbouring areas came to help us.”

Compelling evidence of atrocities emerged from Yemen almost immediately after the air war began in 2015. A camp for internally displaced people was blown up on day three. Numerous independent reports, from the UN, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International among others, have since documented fragments of Paveways in hospitals, markets, schools, and civilian houses. Saudi Arabia has an enormous air force, bought from and maintained by the US and Britain, and from early on began taking out Yemeni infrastructure vital to the survival of the civilian population. It did not disguise its illegal tactics. For example, Saada, a town the size of Cambridge, was designated a legitimate military target and in the words of the UN, “effectively, trapped civilians” were subsequently indiscriminately bombed. Incidentally, the general leading the campaign would later earn global notoriety by organising the murder by dismemberment of Saudi royal-court insider-cum-journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

The UN and NGOs published evidence, including geo-located photos and video, of air attacks on civilian targets. Although the UK government did collate the evidence—the MoD last year recorded over 400 alleged international humanitarian law (IHL) violations since the bombing started—ministers responsible for licensing arms appear to have ignored it. Emails released by the courts to Campaign Against Arms Trade, which won a key element of last year’s judicial review against the government, reveal that Sajid Javid, when he was business secretary, ignored concerns about the risk of civilian attacks from Edward Bell, his most senior licensing official. Earlier, Boris Johnson, as foreign secretary, also signalled he “was content” that the licensing of Paveway components should go ahead.

In London, uncomfortable news of atrocities presented ministers with a problem. Arms sales to Saudi Arabia are sold under the 1985 Al-Yamamah arms deal, the terms of which have never been made public. But declassified government memos reveal the deal commits Britain to rearming the Kingdom, during peacetime and—crucially—wartime. The deal—which has long been mired in corruption, and was lubricated with a BAE slush fund which was tapped by senior Saudis for first-class flights, private school fees and rented flats for girlfriends—remains the bedrock of the military relationship between London and Riyadh.

The British government had a choice: obey international humanitarian laws and break lucrative contracts, or sustain the contracts and try their luck with the law. The Conservative government chose the latter, even offloading the RAF’s own cache of Paveways to the Kingdom during the intensive early months of bombing.

A month before the court judgment, which would reveal the effective relaxation of arms exports to Saudi Arabia, I met a manager at the government’s licencing body, the Export Control Joint Unit, which had—with ministerial oversight—been signing off on Saudi-bound arms shipments for four years. “I’m doing what I’m told and doing my job,” the official said, “but I’m uncomfortably aware that Adolf Eichmann said the same thing.”

Britain’s arming of the Saudi air war in Yemen has produced a moral contagion, flowing from the cabinet office, through Whitehall, all the way to factories in places like Glenrothes.

Three Raytheon staffers employed within the past five years, some with over a decade of service at the Glenrothes site, eventually agreed to speak with me. Scores more declined, suggesting the US International Traffic in Arms Regulations and British rules on official secrets somehow restricted what they could say about potentially politically or commercially sensitive matters.

Two seemed to turn a blind eye to where the bombs they built ended up. One, who worked as a supervisor for Raytheon for over 10 years, sent a reply to questions over email. “The job was taken very seriously by all involved, knew it was important… and I was proud to be a part of it,” he wrote. “From a purely personal and somewhat selfish view when it came to the threat of war [and] wherever or whoever the US were selling their merchandise to, I wasn’t up or down about it as I reckoned from a business end Raytheon would be kept busy.”

“Personally, I don’t give it a moment’s thought,” explained another Raytheon staffer. “If the Arabs want to kill one another that’s their business. We just sell the weapons; we don’t pull the trigger.” I asked whether he recognised the same argument might be applied to a knife salesman who maintains sales to a customer he thinks might use them to kill people. He replied: “That’s the government’s job. If the government issues the licence, its legal,” and then terminated the interview.

“If we didn’t arm them, someone else would,” is a common justification for exports to dubious customers in both the defence industry and the MoD. But it flies in the face of the realities of the Saudi war machine. “The idea that if we stopped selling to Saudi Arabia, they’d just buy bombs off the Russians and the Chinese is just balderdash,” explains John Deverell, a former director of defence diplomacy at the MoD, who has also served as a defence attaché to Saudi Arabia and Yemen. “The Saudi systems are so software dependent—you can’t just plug in any old aircraft and any old bombs.”

A third former Raytheon worker, this one with over a decade of managerial experience at the Glenrothes factory, was prepared to grapple with the more uncomfortable aspects of his old job. He blamed both his former employer and the government for selling and licensing arms to nations that misuse them. Growing up in Clydebank, his brother had joined the Navy and he had attempted to join the RAF as a younger man. “I wanted to defend,” he recalled, “I also wanted to fly fighter planes because it was cool. It was never about killing.” Instead, he trained in Glasgow as a mechanical engineer and has worked in Fife’s dwindling electronics sector ever since, getting his first job just after Silicon Glen peaked.

“I’ve always hated war… I know what war does to people, he said. “I had nightmares as a kid, about nuclear war, and I can still visualise [them]. What it felt like. The physical feeling when I woke up.” Now he moonlights as a karate instructor and warns his students that if they ever instigate violence, he won’t teach them anymore.

He described the “trade off” between the “niggle” he felt as he managed a team to produce 20 “electronic products” vital to the functioning of the Paveway and other Raytheon bombs, and his need to pursue his chosen career, earn a living, support a young family and pay off his mortgage.

“On a personal level it didn’t sit great with me,” he recalled. “I knew what it was going to end up as. I always thought it’s not my job. I’m not a politician. I’m not a commander. I’m not making the decision for when to fire it and where to fire it.”

The former manager stressed how consciousness of the economic decline of the Sottish electronics economy cleaves workers closer to their jobs. “You couldn’t escape it in Scotland,” he said. “[Raytheon] was a good place to work. It was clean, it was warm, and it paid your wages… If anyone did have an issue with the ultimate end product—and there possibly were some over the years—they wouldn’t have lasted long.

“There are few people who can live entirely by their principles. It’s a trade-off between being a husband or a wife verses your belief, whatever it is. Sometimes you’ve got to say that my family comes first—I can’t just walk away.”

Arms dealers have been individually prosecuted for aiding and abetting war crimes overseas through the supply of arms to criminal parties in Sierra Leone, Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia—a principle that was established at the Nuremberg trials.

Drawing on these precedents, the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), a German law firm, last year filed a complaint to the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court against executives from European firms involved in the rearmament of Operation Restoring Hope, the ongoing Saudi air campaign in Yemen.

Sat in her Berlin office, in front of a map of Yemen covered in coloured tags denoting strikes and, where possible, the names of the companies that supplied the bombs in each attack, ECCHR lawyer Linde Bryk talked me through the law and some of her evidence.

“For some of the air strikes included in the complaint we submitted to the ICC, there are remnants of Raytheon bombs found on the ground,” she told me. “We have a lot of data.” She adds that it is enough that the arsenal of weapons you supply can be proven to have “furthered, advanced or facilitated the commission of such offences.”

The complaint seeks the prosecution of Raytheon UK and some executives for allegedly aiding and abetting war crimes. The firm declined to comment specifically on the complaint when I mentioned it in an email, but the individual executives can and—if and when the time comes—will undoubtedly dispute the allegations. At issue is the legal principle of intent, or knowledge about the use of what you are selling. If—a big if—the ICC prosecutor could be persuaded that Raytheon’s ultimate Saudi customers were committing war crimes, then there could be a long hard-fought case with sanctions against the company

and executives.

There is an increasing spotlight on Saudi sales. The UN and numerous NGOs operating inside Yemen have collected data from hundreds of apparently unlawful attacks. Protestors bearing the flags of Yemen and Palestine have turned up at Raytheon’s factory gates in Glenrothes. Whereas at one time, before the court ruling, Raytheon UK was importing the bombs’ warheads from an Italian subcontractor, RWM Italia, that firm’s own licences for direct exports to Saudi Arabia have been suspended by Rome due to the conduct of the Saudi air war.

It is clear, not least because of RAF purchases, that there are still significant ties between Raytheon UK and the government. The firm has met government officials 84 times since 2010 and the US firm hosts an annual Burns Night in parliament for ministers; Gavin Williamson, as defence secretary, told the 2018 Tory conference: “I love Raytheon.”

And that is true. The government loves the arms export business. Former government insiders populate Raytheon’s board, including members of the House of Lords, former ambassadors and Whitehall mandarins. The business brings in a few million to the Treasury and helps subsidise the cost of domestic procurement, certainly in the aircraft sector. Maintaining a strong arms trade is not only about controlling contracting costs and shoring up the balance of payments, but also about projecting the influence of “Global Britain” into the Saudi royal court. In Johnson’s administration, diplomatic clout seems to count for more than other potential objectives, such as global security, human rights and justice for the poorest people in the world.

Depending on your vantage point, British arms sales to Saudi Arabia have substantially different meanings. For the British government it is about power and influence. For the people of Glenrothes it is about decent—now rare—jobs. For British arms companies, it is about new deals, shareholder returns, management bonuses.

But there is of course another way to see things. From the perspective of the friends and relatives of the 100,000 people killed since 2015, the sense of injustice will never go away.

“I want these innocent victims to have their rights according to… law and justice,” Mohammed Busaibis told a documentary crew who visited him in the remote village of Al-Wahijah shortly after his son’s wedding was hit there on 28th September 2015, killing 131 civilians. “I am suffering sorely from injustice of these arrogant people.”

Source: Prospect Magazine, Edited by Website Team